The espresso machine blinks awake, a green light in the half-dark of morning. I slip in a capsule, press the button, and watch the dark ribbon pour into a cup I’ve owned longer than any apartment. The first sip is both signal and permission: the day may begin.

Only lately, the ritual shares space with an unease I can’t quite drink away. What, exactly, did I just set in motion—what energies and miles, what metals and plastics, what fields and factories did this ounce of convenience require? We live in the generation of the button, an age that avoids resistance, where even the smallest effort feels like too much. We prefer the quick click to the slow stir, the promise of no mess to the smallest inconvenience—as if rinsing a coffee maker were an act beneath us. Capsules fit this age perfectly: elegant, sealed, and instantly forgotten.

There’s a temptation to shrug it off. Coffee is ancient, everyday, unremarkable. Yet capsules have turned an ordinary act into a parable of modern consumption—how we design convenience, outsource complexity, and struggle to measure the fallout. Follow a single capsule back through its supply chain and forward into its afterlife, and you find yourself navigating chemistry, policy, and habit. It’s a small object that touches nearly every system we’ve built.

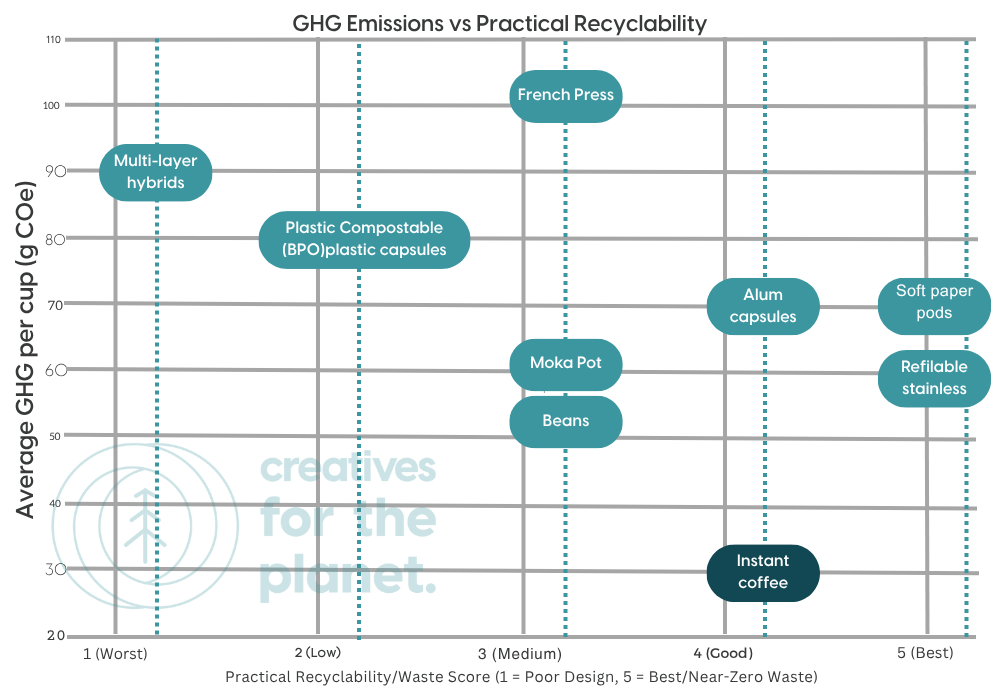

Environmental accounting loves numbers. Life-cycle assessments, those dense scientific models that quantify every gram of carbon, attempt to capture the story of a single cup: the farming and roasting, the packaging and transport, the electricity to heat the water, and the end-of-life fate of the pod or paper or grounds. The results are humbling. The coffee itself—not the capsule—is usually the main culprit, because the quantity used per serving drives most of the footprint. Brew with precision and you may pollute less with a pod than with an overfilled French press whose leftovers go cold and down the drain.

Yet the calculus changes when we look at waste instead of emissions. Capsules concentrate environmental cost in a tangible leftover. Whether that object becomes resource or residue depends on local infrastructure: if sorting plants can capture small items, if aluminum and polypropylene are processed nearby, and whether “compostable” actually means accepted in your city’s compost stream. Too often, the green capsule still ends up in a gray bin.

Every capsule is a door into a much larger story of energy, waste, and responsibility.

The capsule world is no monolith. Aluminum pods, the hallmark of the category, are energy-intensive to produce but infinitely recyclable—if they are collected and melted down. Polypropylene pods are lighter to make but often too small for the optical sorters that decide the fate of our waste. Compostable bioplastic versions sound promising but need the high heat and controlled conditions of industrial composting. The older multi-layer hybrids, a fused sandwich of plastic and aluminum, remain a design dead end, nearly impossible to separate and recycle.

And then there are the soft “teabag” pods—Senseo, E.S.E.—simple pouches of ground coffee between thin paper layers. They occupy an in-between space: portioned like a capsule, but made of familiar materials that, if truly plastic-free, can join food waste and return to the soil. Their potential depends entirely on honesty in labeling.

Across all these methods, the same truth holds: the footprint is as much about how we use them as what they’re made of. Overfilling kettles, overdosing coffee, or letting half a pot go cold can negate the benefit of any design innovation.

Long before any capsule clicks into place, the story of coffee is already heavy with consequence. Cultivation in tropical regions can mean deforestation, intensive water use, pesticides, and precarious labor. Organic and Fair Trade certifications soften those edges, but capsules tend to limit choice to what the brand offers. Refillable metal capsules—those quiet rebels of the system—return that freedom to the consumer, allowing you to fill a stainless shell with whatever beans align with your ethics and taste. Used hundreds of times, they nearly erase their own manufacturing footprint.

The major players have learned to sound sustainable. Nespresso touts capsules made with over eighty percent recycled aluminum and the spread of curbside collection in France. Keurig points to its switch to polypropylene #5, the same resin used for yogurt containers. Boutique roasters print leaves and soil tones on their compostable pods, invoking the promise of circularity. But recyclability on paper is not the same as recycling in practice. Access, participation, and infrastructure decide the real outcome.

Regulators have begun to close that gap between marketing and materiality. In the United States, Keurig was fined for overstating recyclability. In the United Kingdom, advertising authorities banned claims that blurred industrial and home composting. And in Europe, a sweeping new packaging law requires that by 2030 all materials be not only recyclable in theory but recycled at scale in reality. Responsibility, once placed solely on consumers, is shifting toward proof at the system level.

The best method is never universal—it depends on what your city, your habits, and your conscience can support.

Still, it is in the kitchen that policy becomes habit. A French press, beloved symbol of artisanal coffee, can be close to zero waste when used sparingly, yet its romance often leads to wasteful excess. A moka pot or espresso machine, with small cups and tight dosing, balances efficiency and ritual. Instant coffee—dismissed by purists—remains a surprisingly clean choice, with its minimal energy use and long shelf life.

Single-serve capsules, for all their flaws, are efficient by design. Whether that efficiency translates into sustainability depends on what happens afterward. Aluminum performs well in places where it’s truly recycled; elsewhere it’s just bright waste. Plastic pods are only recyclable in a minority of regions. Compostable pods can shine when cities collect organic packaging but quickly turn into contaminants where they don’t. Multi-layer hybrids are almost impossible to redeem. Refillable capsules stand out when genuinely reused, marrying convenience with conscious sourcing. And soft paper pods—made of pure cellulose, composted in an industrial facility or even a home garden—quietly emerge as one of the most balanced options. Low energy in the machine, precise portions, and a body that can return to the soil: a small victory for a large problem.

Even as climate data dominates, smaller concerns persist: microplastics, aluminum exposure, water purity. These issues matter, but the bigger story is design. The most sustainable cup is the one that uses simple, durable materials and devices built to last. In that sense, the true luxury is not innovation but endurance.

Harmony is not found in a single choice, but in the repetition of smaller, less harmful ones.

It’s easy to treat all this as a private moral dilemma, yet personal habits are exactly where public rules take effect. When regulators define compostability or punish deceptive claims, they translate awareness into law. And when consumers adjust their routines—refusing to confuse “recyclable” with “recycled”—they push those laws further. The loop of responsibility runs both ways.

I finish the cup and translate thought into practice. From now on, I’ll match my method to my context: a refillable capsule when I need speed, a moka pot when I have time, instant when efficiency matters, and soft paper pods when simplicity and composting align. Each choice is small, but none are meaningless.

The point is not purity—it’s awareness. To recognize that every cup contains not only caffeine but carbon, labor, and consequence. To insist that companies match words with proof, and that regulators keep them honest. We’ve become a culture of buttons, impatient with effort, yet the planet’s balance may depend on our willingness to make one—to rinse, to think, to choose.

Harmony isn’t achieved once; it’s rehearsed daily, cup by cup, by choosing less harm when we can see it clearly. Tomorrow, the machine will blink, the water will heat, and the day will pose its questions. I’ll answer one before I take the first sip.