Over the course of a trimester in Ibiza, five secondary schools stepped out of their regular timetable and into a sequence of deliberately connected actions. It was not a one-day event or a symbolic gesture. It was a creative process.

In total, 265 students from IES Sant Agustí, IES Isidor Macabich, IES Santa Maria d’Eivissa, IES Quartó de Portmany and IES Balàfia took part. Each school carried out its own cleanup action in nearby natural environments. The sum of those independent interventions resulted in 231 kilograms of waste collected from beaches and landscapes we usually associate with beauty, not debris.

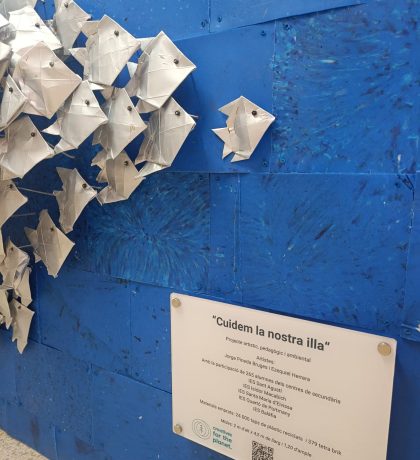

The project is part of the educational program by Creatives for the Planet titled “Cuidem la nostra illa” – “Let’s Take Care of Our Island,” funded by the Sustainability Fund of Six Senses Ibiza. From the outset, it was conceived as an artistic, pedagogical and technological initiative. The intention is clear: confront the reality of waste, understand the system that generates it, transform part of it into something visible and share it with society.

After the cleanups, the work continued inside the classrooms. The team from Creatives for the Planet did not arrive with a finished artwork. They arrived with questions.

In workshops led by Harmony Hita Torres, the discussion revolved around circular economy. Where does our waste go? What does it really mean to clean? Which “R” is the most important? Which packaging has the worst circularity? What are polymers? Why can some plastics be recycled together while others cannot? What percentage of everyday plastic objects actually returns to the recycling system? Who is cleaner, the one who cleans the most or the one who litters the least?

Jorge Pineda Bruges, creative director of the organization, is direct about it. “It’s very educational,” he says of the hands-on process. “They learn the importance of not mixing polymers. If they don’t have the same components, they don’t melt together.” He often asks students to look at the plastic objects they are carrying and guess which ones are recyclable. The conclusion is uncomfortable. “Less than five percent of what they have is truly recycled. Not their shoes. Not their polyester backpack. Not their pen. The problem is enormous.”

The workshop does not remain theoretical for long.

In the school courtyard, students work with the Plustic Lab shredder bicycle. They pedal, and the movement activates blades that shred plastic caps into small flakes. The machine quickly becomes a focal point. Even during break time, students from other classes come to try it and contribute their part. The dynamic is energizing. Teenagers who might struggle to remain attentive during a long talk pedal with focus and intensity, watching the transformation in real time and asking for their turn on the bike.

From there, the material enters a new phase. The shredded caps are weighed, approximately 350 grams per mold, and placed into 3-millimeter frames. They are heated, pressed to achieve a uniform thickness, cooled and removed from the molds. They are then cut and fixed onto a wooden structure. In total, 49 kilograms of caps form a textured blue seabed.

At the same time, students work with 490 discarded tetrapaks that they bring from home. They open them, clean them and transform them into fish during the classroom sessions. Some sign their piece on the back before handing it over. Each fish is an individual contribution that will later become part of a larger whole, a major co-creative artwork.

For Ezequiel Herrera, artist and member of Creatives for the Planet, the choice of material is never accidental. “As an artist I express an idea. The material follows the idea,” he explains. He works with acrylics, clay, wood, cages, coins, medicine packaging or plastic depending on what he wants to convey. In this case, the tetrapak carries its own meaning. “It is the packaging with the worst circularity. Recycling it requires much more energy and water than other materials such as metal or glass, which is 100 percent recyclable,” he says. If the world doesn’t know what to do with it, art will.

The final step takes place in the studio, where Jorge and Ezequiel design and assemble the nine-square-meter mural. The pressed plastic panels create the seabed. The 490 fish made by the students are mounted in a dense formation, forming a sculptural bank that moves across the surface. The work has relief, depth and shadow. It is not a flat image but a constructed three-dimensional environment.

Jorge insists on that dimensionality. “I’ve never made a piece without tridimensionality,” he says. “This mural has relief like all the previous ones.” The process, he adds, is complex not only conceptually but technically: selecting thousands of caps with the students, shredding them, molding them, pressing them, cutting them and finally fixing each element in place. The transformation is meticulous.

The structure of the project can be followed step by step in our summary video.

First, direct contact with the issue through cleanups in natural environments.

Second, a classroom workshop that places waste within the logic of circular economy and consumption habits.

Third, artisanal, mechanical and material transformation through shredding, heating and reformulating plastic and tetrapak packaging.

Fourth, artistic integration, where student-created elements and recycled material become a monumental mural.

The artwork will travel to all participating schools, will even take the stage at TEDxIbiza, and will finally be exhibited at the Six Senses farm, whose Sustainability Fund financed the project.

Students know their fish are part of it. “I love co-creating,” Jorge tells them. “Alone, I couldn’t do this.” More than 270 people, including teachers and the team, took part. The artwork belongs to all of us.

No one involved claims that this will solve the plastic problem. A shredder bicycle will not reverse the climate crisis. A mural will not alter global supply chains. The statement is more modest and at the same time more serious: experience integrates and changes the perception of problems and what a person considers normal.

Those who have separated polymers understand recycling differently. Those who have cleaned a beach rarely litter it afterward. Those who see their signed fish integrated into a traveling artwork understand the effort and the collective power of art.

The final mural, with its seabed of shredded caps and its school of fish made from discarded packaging, remains as a visible result of co-creation between five schools united by a shared concern.

And once you have seen a bank of fish rise from what you threw away, it becomes harder to believe that your actions dissolve without consequence.

Text: Sophia Brucklacher

Conversation: Art, Waste and the Classroom

After months of cleanups, workshops and construction, the mural now stands as a collective result. But what shaped the thinking behind it? What does it mean, as artists, to work with waste alongside teenagers?

I spoke with Jorge Pineda Bruges, creative director of Creatives for the Planet, and Ezequiel Herrera, artist and member of the organization, about material, education, and the limits of recycling.

Sophia Brucklacher: You worked with 49 kilograms of shredded plastic caps to create the seabed. As artists, how does your tactile relationship to the “canvas” change when you use waste instead of traditional materials like oil paint or clay?

Jorge Pineda Bruges:

It’s curious – I was never very much into painting, but I always liked creating three-dimensional things. In fact, I’ve never made a piece without tridimensionality. This mural has relief like all the previous ones.

Not only is it more fun for me, I also consider it a much more complex process. First, we have to transform the selected elements. In this case, to create the seabed, we selected thousands of caps with the children. Then we shredded them, placed them into 3 millimeter molds using around 350 grams per mold, heated them, pressed them so they all had the same thickness, then cut them and screwed them onto the mural. It’s a long technical process.

Ezequiel Herrera:

As an artist, I express an idea, and that idea guides the result I want to achieve. The material is selected according to the idea. I work with acrylics and brushes to create figurative paintings, with clay to make sculptures, with wood for structures, with cages, coins, medicine packaging, plastic. It all depends on what you want to transmit.

Nothing changes or conditions me in the moment of creating. The material serves the idea.

Sophia Brucklacher: The mural presents a “bank of fish” made from 490 tetrapaks. Is there a deliberate irony in using commercial packaging to represent marine life often displaced by that same commerce?

Jorge Pineda Bruges:

For me, art is the most powerful communication tool. It speaks for itself, and its message lasts over time. That’s why all our sculptures carry a deep message.

In this case, as a diver, I also want to remind people of the beauty of seeing a real bank of fish – something I don’t usually find in Ibiza’s waters anymore.

Ezequiel Herrera:

Everything ends up in the sea.

Tetrapak is a highly contaminating material, including the way it is recycled, because of the different layers it contains. Precisely for that reason, it becomes a good material to retain and transform into a work of art. It stays here. It becomes permanent. It is removed from its waste cycle.

If the world won’t know what to do with it, then art will.

Sophia Brucklacher: This project defines itself as “art-cycling.” Do you believe art is a more effective tool for environmental awareness than scientific data?

Jorge Pineda Bruges:

They are different things. I see art-cycling as a very powerful communication tool. Science inspires us and gives us knowledge so that we can express our concerns about taking care of our home.

Ezequiel Herrera:

I believe art can be more effective than data. Art moves something inside the human being. When you create, you generate something that did not exist before.

And when that creation is combined with collecting waste – seeing the problem in situ – the combination is fantastic. You create while helping to resolve a problem. It is liberating and gratifying.

Sophia Brucklacher: The Plustic Lab shredder bicycle is low-cost technology but high impact. What happens when you introduce this kind of collective mechanical creation into a school courtyard?

Jorge Pineda Bruges:

The students enjoy it enormously. Even during break time, students from other classes come to use it. It’s very educational. They learn directly the importance of not mixing polymers, because if they are not the same type, they don’t melt together. That makes them question things.

We often ask them to look at the plastic objects they have and ask which of those are recycled. They realize that less than five percent of what they have actually is. Not their shoes, not their pen, not their polyester backpack. Unfortunately, we generally don’t know this. The problem is enormous.

Ezequiel Herrera:

The idea is magnificent. We are talking about teenagers with almost infinite energy. It is difficult to keep them seated in a talk for more than fifteen minutes. But pedaling energetically and seeing how they themselves transform waste into raw material — that works. It’s an intelligent dynamic.

At their age, we need to give them tools to act. If you put them inside a refrigerator with a cellphone, they will do nothing. If you motivate them with a bike, a challenge, an action — they respond.

Sophia Brucklacher: You worked with 265 secondary students. Many say teenagers are apathetic, yet here they got their hands dirty. What surprised you most?

Jorge Pineda Bruges:

The majority get involved. These are fun extracurricular actions. We believe that fun attracts, and that creativity has something almost psychomagical — it integrates concepts more directly.

When you clean a beach, you will never again throw trash in a natural environment. Through action, concepts stop being abstract and become ideals.

Ezequiel Herrera:

They were mostly interested and motivated to use tools. Human beings naturally want to touch, investigate, manipulate. If you support them, give them space and motivation, they respond very well. It depends on the tools that institutions and adults provide for their development.

Sophia Brucklacher: How does the artistic process help make abstract concepts like circular economy tangible for a 15-year-old?

Jorge Pineda Bruges:

Harmony does wonderful work in transforming the classroom into a dynamic learning space. In her theoretical workshop, the students first absorb knowledge and statistics. They understand where materials come from, where packaging goes, and how consumer responsibility determines that path.

Our message is always to reduce. That requires responsibility and knowledge. The best waste is the one that does not exist.

Ezequiel Herrera:

The artistic process is the backbone of understanding circular economy. They understand by doing. By collecting, recycling, transforming. Through practical tasks, they are literally performing circular economy.

Sophia Brucklacher: Each student’s tetrapak fish becomes part of a monumental mural that will travel across the island to TEDxIbiza. What does that mean for them?

Jorge Pineda Bruges:

I explained to them that I couldn’t do this alone. I love co-creating because you move faster and can create more elaborate and larger works. The impact is greater because we were more than 270 people, including teachers and our team. Alone, I would not have achieved it. They know that. And I feel we are all very proud.

Ezequiel Herrera:

We had the idea that they sign their fish on the back. They show motivation and interest in being part of a large-format work. Everyone wants to be part of something. Who wouldn’t like to stand in front of a great painting one day and say to their child, “That brushstroke, I did that one.”

Sophia Brucklacher: If certain waste in our society is still difficult to avoid, how does this project teach young people to make that waste meaningful rather than simply garbage?

Jorge Pineda Bruges:

At the end of the process, they understand the dimension of the problem. We want to awaken awareness so that in the future they are the ones who can change these irresponsible actions that a devastating capitalism ignores – as if the planet were infinite and we had a backyard where waste disappears.

Ezequiel Herrera:

If something is difficult to recycle, one of the most accurate responses is to turn it into art. In that way, the material is interrupted in its cycle and fixed in a new essence: to be art.

Sophia Brucklacher: Thank you very much.